A Big Enough Lie

Named by the Guardian one of the best books of 2015.

Named by Literary Hub one of the most important books of the last twenty years.

Awaiting a TV talk show appearance, John Townley is quaking with dread. He has published a best-selling memoir about the Iraq War, a page-turner climaxing in atrocity. In a green room beyond the soundstage, he braces himself to confront the charismatic soldier at the violent heart of it. But John has never actually seen the man before—nor served in Iraq, nor the military. Even so, and despite the deception, he knows his fabricated memoir contains stunning truths.

By turns comic, suspenseful, bitingly satirical, and emotionally potent, A Big Enough Lie pits personal mistruths against national ones of life-and-death consequence. Tracking a writer from the wilds of Florida to New York cubicles to Midwestern workshops to the mindscapes of Baghdad—and from love to heartbreak to solitary celebrity—Bennett’s novel probes our endlessly frustrated desire to grab hold of something (or somebody) true.

"... as truthful a book about the Iraq calamity as there is to read. Lacerating and heart-breaking, it’s a tour de force romantic melodrama in the take-no-prisoners style of Pat Conroy’s The Lords of Discipline." —The Rumpus

Read the reviews

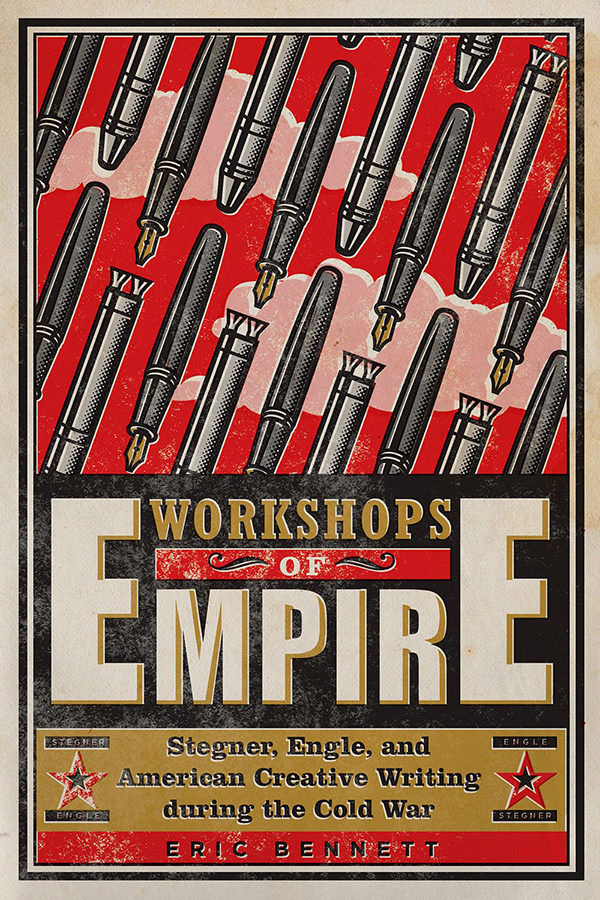

Workshops of Empire

Stegner, Engle, and American Creative Writing during the Cold War

During and just after World War II, an influential group of American writers and intellectuals projected a vision for literature that would save the free world. Novels, stories, plays, and poems, they believed, could inoculate weak minds against simplistic totalitarian ideologies, heal the spiritual wounds of global catastrophe, and just maybe prevent the like from happening again. As the Cold War began, high-minded and well-intentioned scholars, critics, and writers from across the political spectrum argued that human values remained crucial to civilization and that such values stood in dire need of formulation and affirmation. They believed that the complexity of literature—of ideas bound to concrete images, of ideologies leavened with experiences—enshrined such values as no other medium could.

Creative writing emerged as a graduate discipline in the United States amid this astonishing swirl of grand conceptions. The early workshops were formed not only at the time of, but in the image of, and under the tremendous urgency of, the postwar imperatives for the humanities. Vivid renderings of personal experience would preserve the liberal democratic soul—a soul menaced by the gathering leftwing totalitarianism of the USSR and the memory of fascism in Italy and Germany.

Workshops of Empire explores this history via the careers of Paul Engle at the University of Iowa and Wallace Stegner at Stanford. In the story of these founding fathers of the discipline, Eric Bennett discovers the cultural, political, literary, intellectual, and institutional underpinnings of creative writing programs within the university. He shows how the model of literary technique championed by the first writing programs—a model that values the interior and private life of the individual, whose experiences are not determined by any community, ideology, or political system—was born out of this Cold War context and continues to influence the way creative writing is taught, studied, read, and written into the twenty-first century.